The NSF–DOE Vera C. Rubin Observatory in Chile brings the night sky to life like never before. During the first 10 years of operation, Rubin Observatory will conduct the Legacy Survey of Space and Time creating the widest, fastest and deepest views of the night sky ever observed. It will provide a trove of data that is hosted at the U.S. Data Facility at SLAC and will be available to the scientific community to collectively discover cosmic mysteries.

Discover first images revealed

The hidden universe

If you ask a physicist what the universe is made of, the answer might surprise you. Just 5 percent of the universe is ordinary matter, the atoms that make up stars, planets, and everything we see. The remaining 95 percent something else entirely: dark matter and dark energy, mysterious matter and forces that shape the cosmos yet remain largely unknown. While researchers have developed many theories about what these unseen components might be, the true nature of most of the universe is still a mystery.

To get to the bottom of this and other cosmological questions, an international team built the NSF–DOE Vera C. Rubin Observatory. Its mission: to conduct the Legacy Survey of Space and Time (LSST), a decade-long effort to map the Southern hemisphere sky in unprecedented detail.

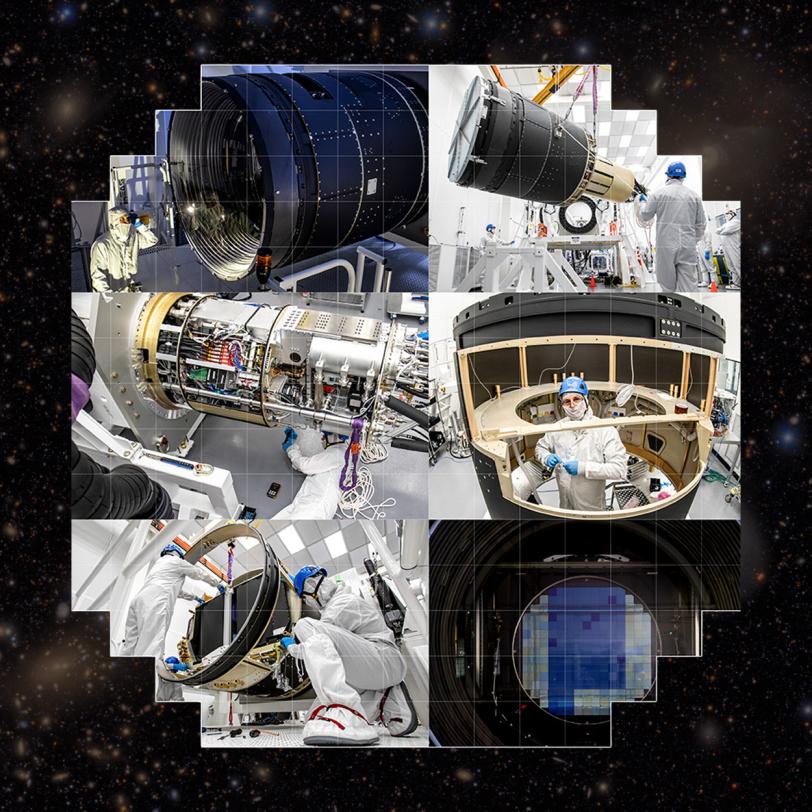

At the heart of that project is the largest digital camera ever built, the LSST Camera. Now installed on Rubin’s Simonyi Survey Telescope, it will capture a new image of the sky every 40 seconds, allowing scientists to detect changes across the universe as they happen.

LSST Camera explainer

An overview of the world’s largest digital camera

Roughly the size of a car, it’s a large-aperture, wide-field optical camera that is capable of viewing light from the near ultraviolet to near infrared wavelengths.

The LSST Camera in numbers

| Length | 14.73 ft (4.49 m) |

| Height | 5.5 ft (1.65 m) |

| Weight | 6635 lbs (3010 kg) |

| Pixel Count | 3200 megapixel |

| Wavelength Range | 320–1050 nm |

Note: 1 nm (nanometer) = 10-9 m or one-billionth of a meter

The lenses

Light from the night sky falls on a series of three giant lenses; the front lens alone is more than five feet tall, making it the world's largest lens for astrophysics. Together with the observatory’s mirrors, these lenses gather light from an area of sky equivalent to about 45 full moons.

The filters

The camera contains a carousel that holds its filters. Each of the filters can be individually swapped out in under two minutes and up to four times a night with the double-rail auto changer. In total, the system includes six specialized filters that can be rotated in front of the focal plane. This allows researchers to analyze particular bands of light, from ultraviolet to the near-infrared, separately from other wavelengths.

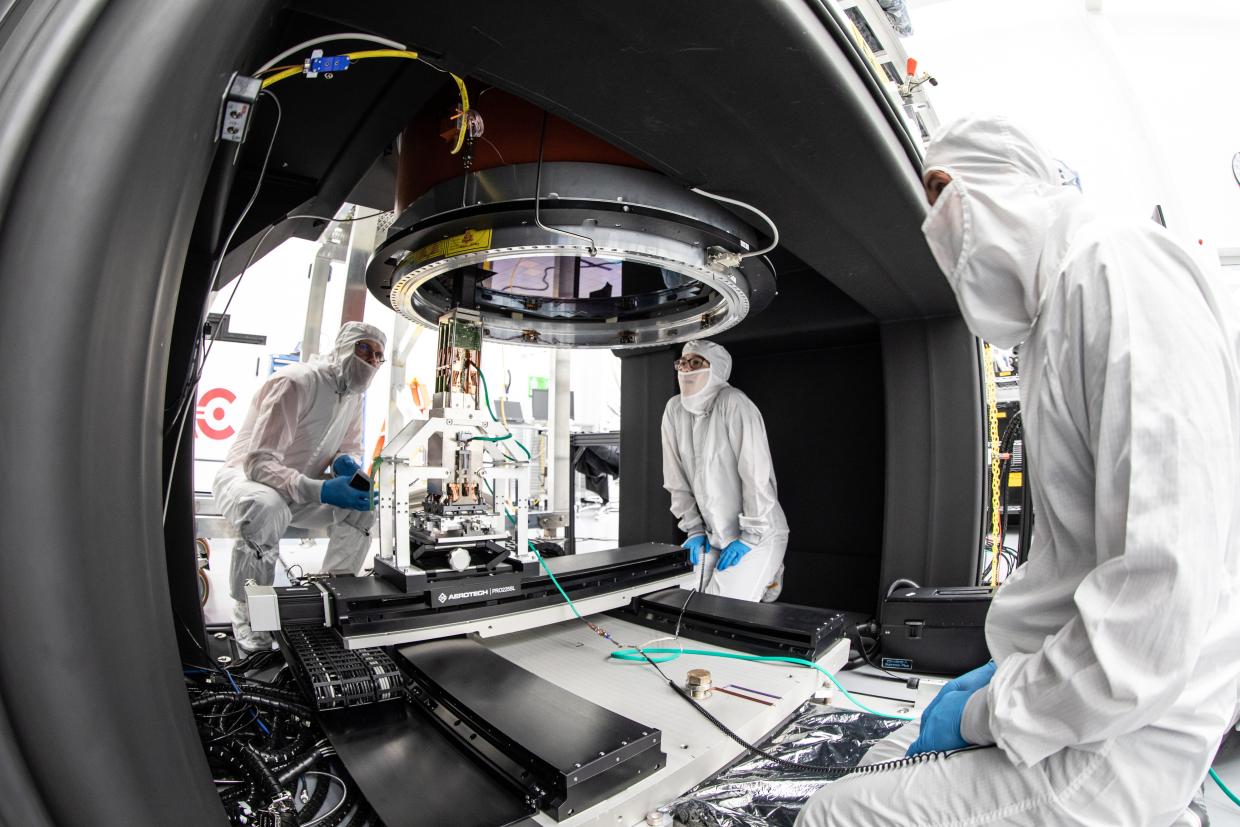

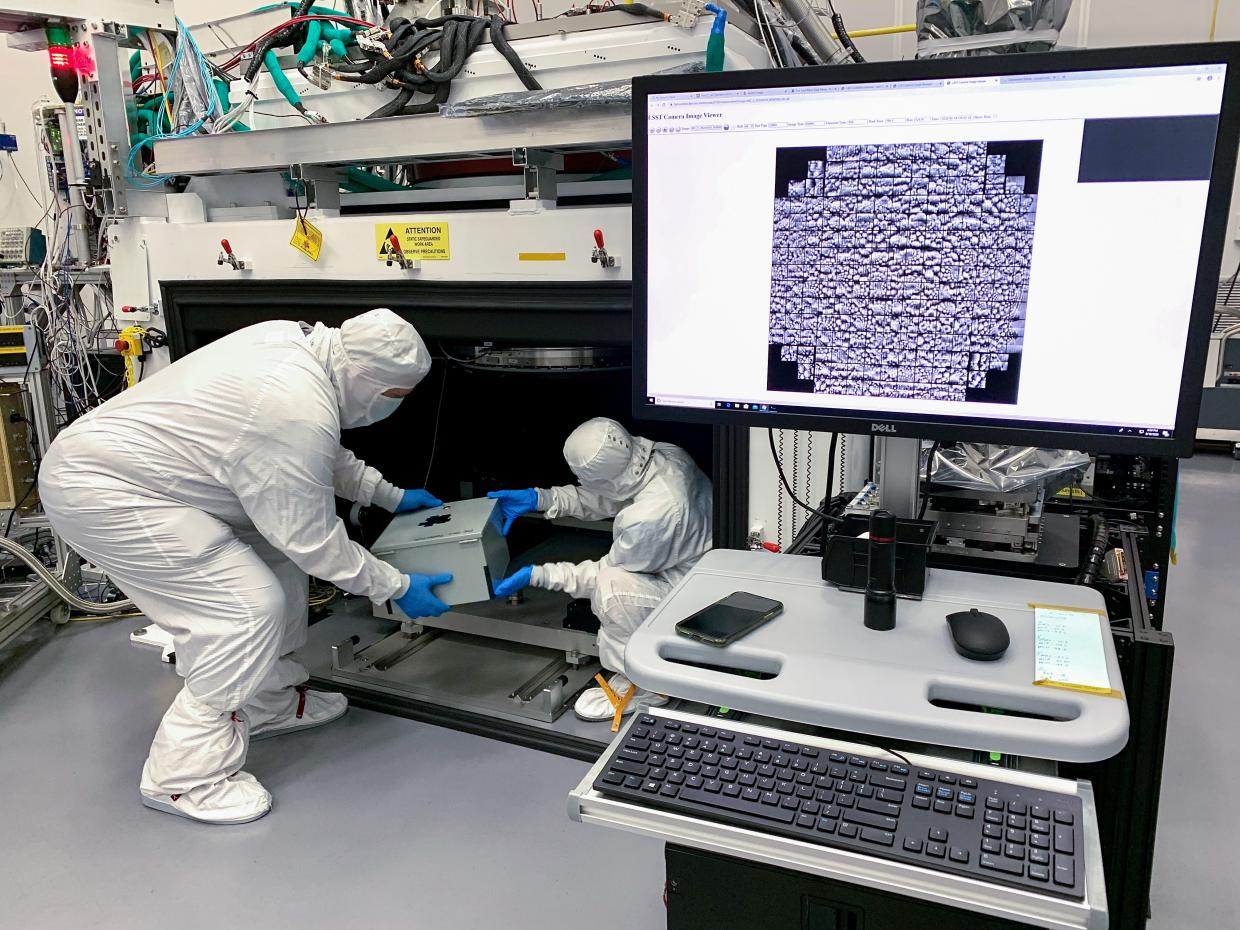

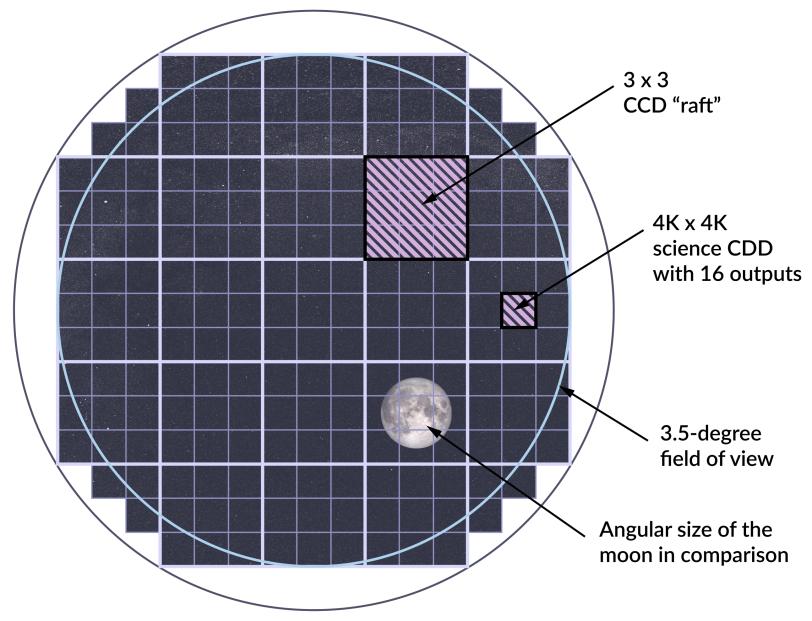

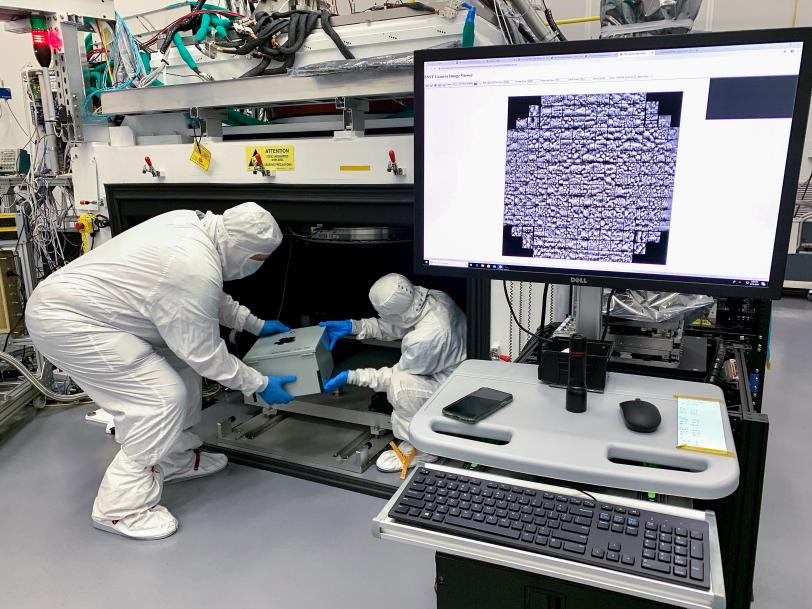

The focal plane and cryostat

The light is focused onto an array of 189 charged-coupled device (CCD) sensors, arranged in a total of 21 3-by-3 square arrays mounted on platforms called rafts. They make up the 25-inch diameter, 3.2 gigapixel focal plane. It sits inside a vacuum chamber, called a cryostat, with a refrigeration system that keeps the sensors at minus 148 Fahrenheit to reduce noise.

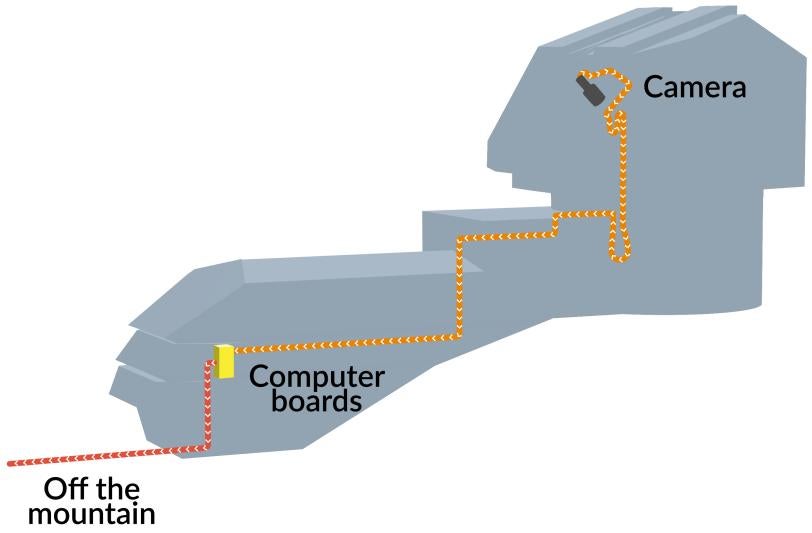

Data acquisition system

Fiber optic cables at the back of the camera carry 10 terabytes of data a night down the telescope to a custom-built data acquisition system. The data acquisition system will also maintain a buffer of thousands of images gathered over several nights – just in case the observatory loses contact with the outside world. It is the first time we will catalog more galaxies than there are people on Earth.

Ready set processing

A look inside the data processing infrastructure built by the Rubin Observatory.

Creating a moving picture of the universe

The Rubin Observatory takes an image about every 40 seconds every clear night and will continue this cadence for an entire decade. Researchers will pore over the data looking for evidence of dark matter and dark energy. The data from the LSST Camera will also help them study how galaxies form and evolve, catalog asteroids, and search for other objects moving in and through our solar system. Researchers will examine the changing night sky to better understand variable stars, see galaxies in the midst of being eaten up by black holes and watch stars explode in bright supernovae. In myriad ways, the LSST Camera will expand our understanding of the universe in which we live.

LSST Camera: Galaxies of data

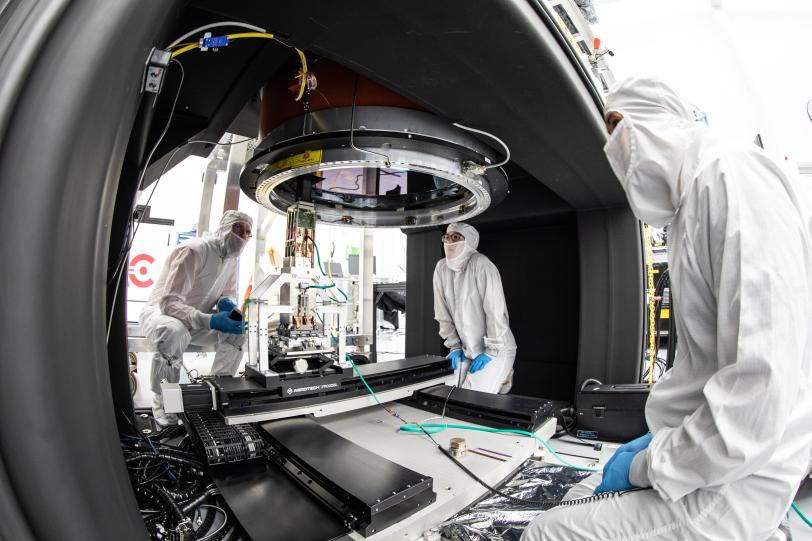

Follow the LSST Camera’s journey, starting with 10 years of construction at SLAC to its installation on the Simonyi Survey Telescope of NSF–DOE Vera C. Rubin Observatory. For more photos visit SLAC's Flickr LSST Album Collection page and Rubin Observatory gallery

Installing the LSST Camera

Vera C. Rubin Observatory Aerial

NSF–DOE Vera C. Rubin Observatory LSST Camera focal plane build

Inspecting the L3 lens

Pinhole projector from LSST Camera

2025_0409_SRCF_USDF_Rubin_LCLS_Data_Orrell-87.jpg

Video collection

Explore a collection of videos that detail the 10-year journey of building the camera and behind the scenes stories.

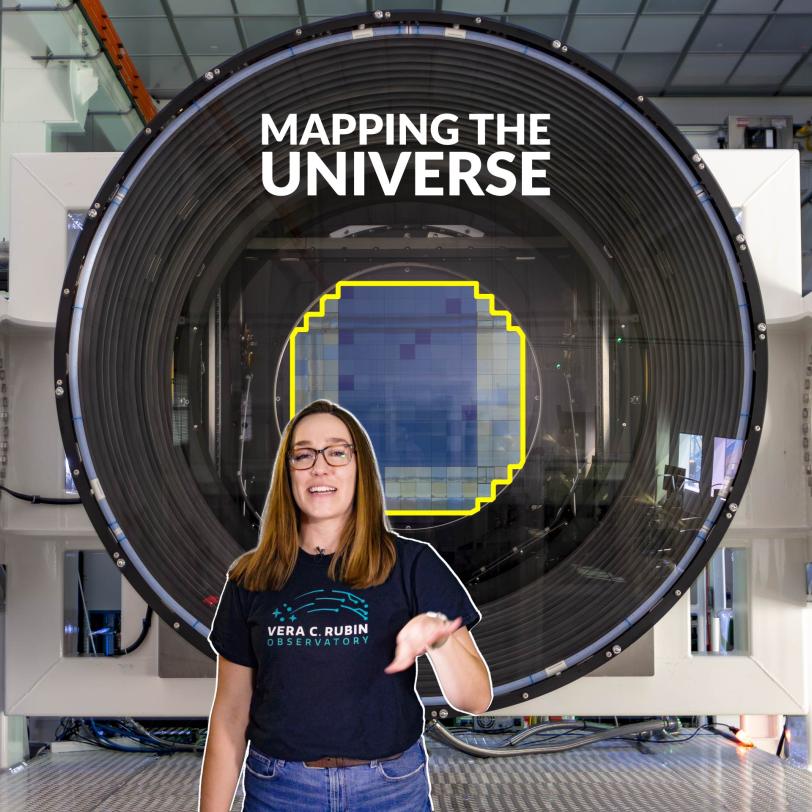

Explainer Public Lecture

Mapping the Universe – Hannah Pollek

LSST Camera: 8 year time lapse